Briefing Note: Addressing Funding Inequities, Accountability, and Small Business Challenges in New Zealand’s Primary Healthcare Sector

Introduction

New Zealand’s primary healthcare sector is facing significant challenges due to misalignments in funding models, rising service demands, systemic inequities, and regulatory burdens.

Silverdale Medical, a primary care practice serving a diverse patient base in Northern Auckland, exemplifies these challenges. This briefing note outlines key issues affecting the practice, including the financial strain caused by outdated funding assumptions, the need for accountability in capitation payments, the impact of employment policies on small businesses, the growing disillusionment among primary care providers, and the urgent need for the development and integration of allied health professions. It concludes with strong recommendations aimed at creating a more equitable, sustainable, and accountable primary care system.

1. Complexity and Cost of Care for CSC (Community Services Card) Holders Increased Service Demand and Misalignment with Funding Formula

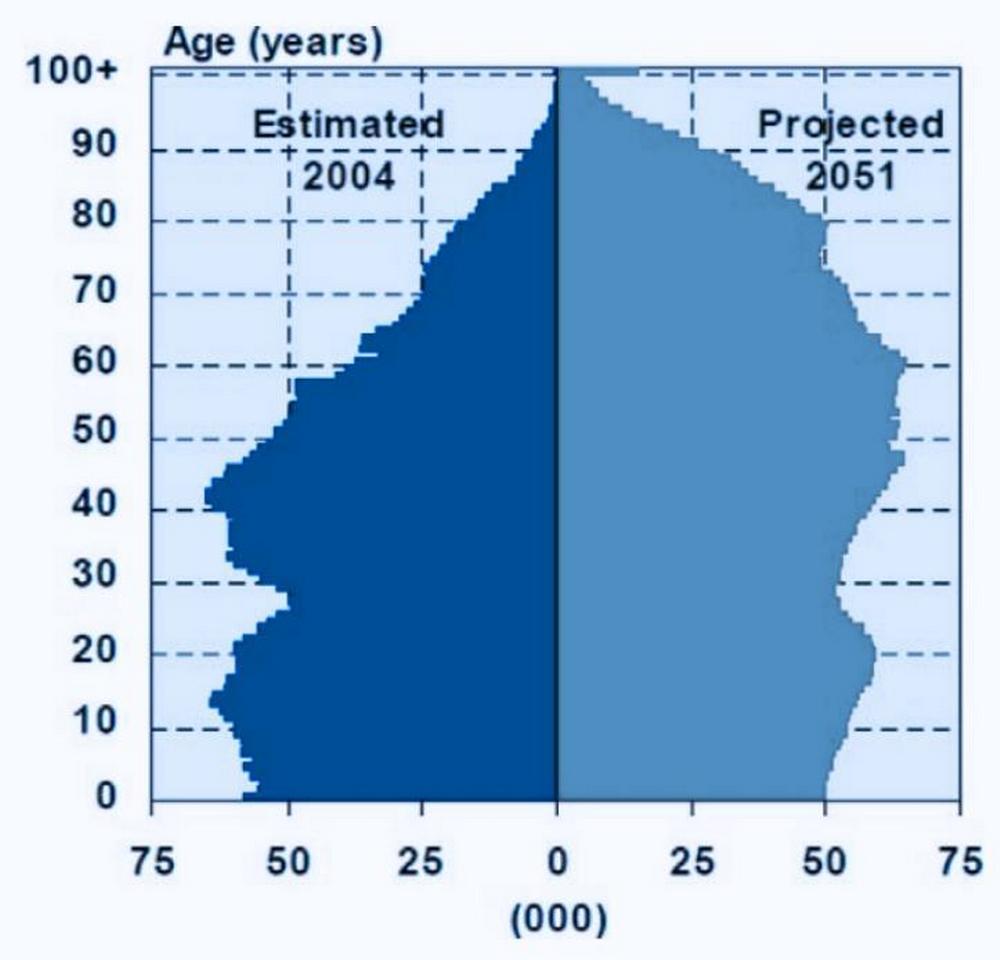

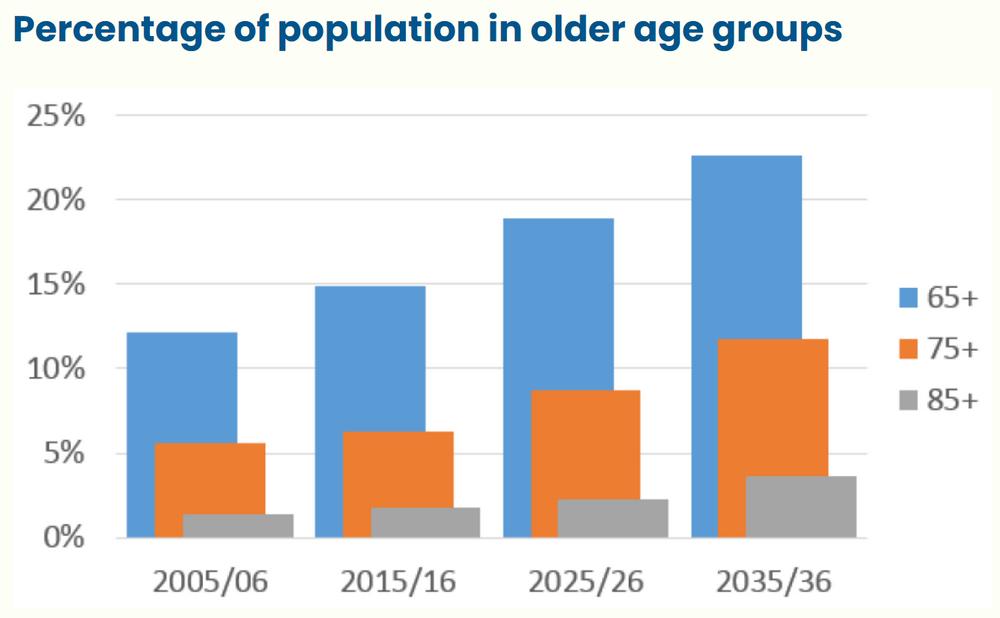

The current funding model for Community Services Card (CSC) holders was developed under the assumption that patients would require an average of 2.2 appointments per year. The CSC funding was calculated to cover the portion of the patient’s fees above the fixed amount paid by the patient. However, actual utilisation has consistently exceeded this assumption, averaging

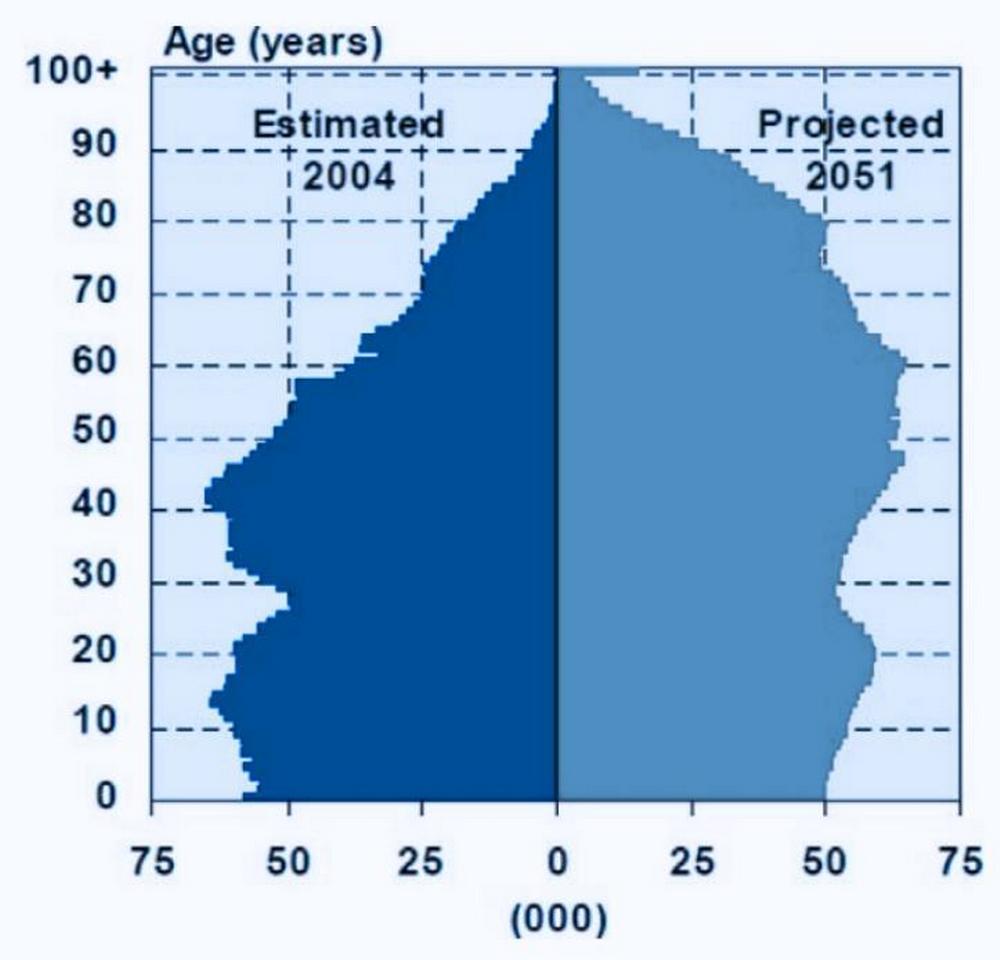

3.0 appointments per year for several years. Recently, this utilisation rate has surged to 4.6 appointments per year, primarily due to the aging population of CSC cardholders over the age of 65, who require more frequent and complex care.

Adding to this challenge, it is important to note that since 2016, annual funding increases for primary care capitation have been below the Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA). As a result, even the originally anticipated 2.2 appointments per CSC patient are not fully funded, exacerbating the financial strain on practices like Silverdale Medical, which are now significantly underfunded relative to actual demand and cost of providing care.

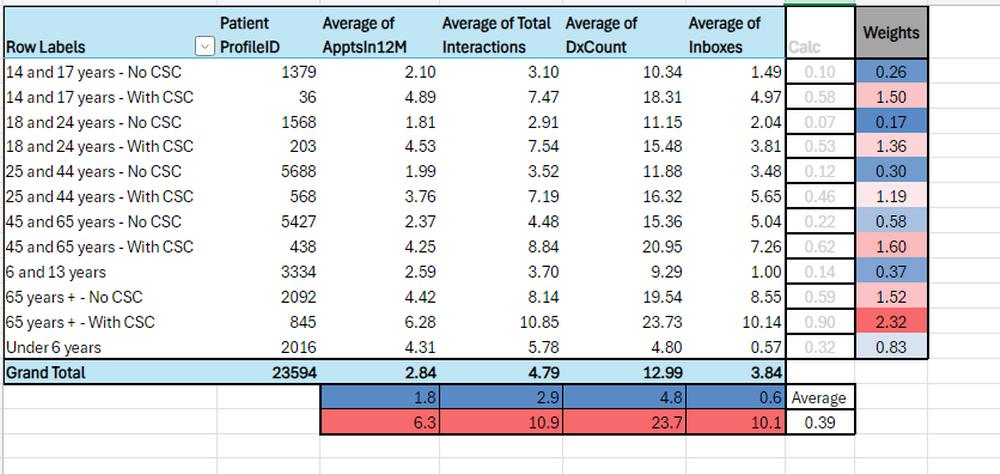

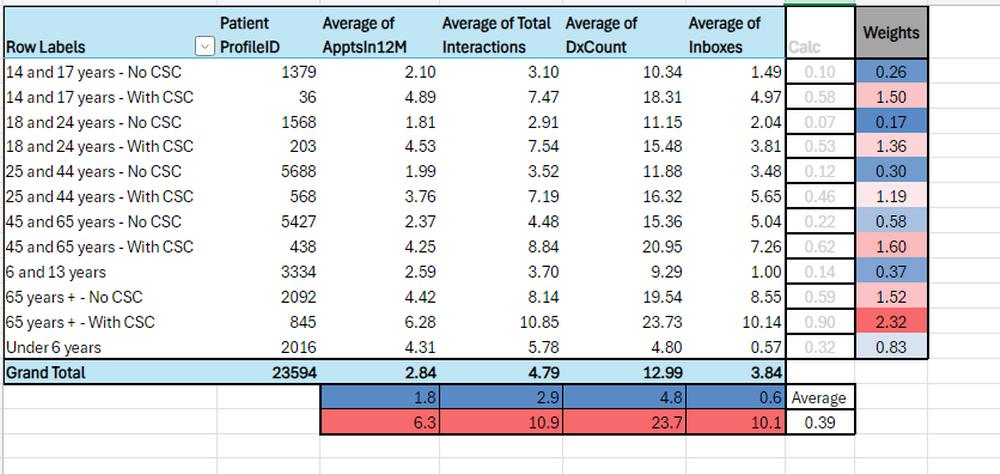

The following table shows the breakdown of patient complexity and service demand across different age groups, highlighting the disparity between CSC holders and non-CSC holders:

The data underscores the significantly higher service demand among CSC holders, particularly those aged 65 and older, who average 6.28 appointments per year compared to 4.42 for non- CSC holders in the same age group.

As well, of note in 28.8% of patients over 65 years in this practice in the very middle-class communities of Northern Auckland qualify for the CSC Card. Of significant concern is the expectation that as those currently aged 55-65 retire, many more will become eligible for the CSC Card. Contrast the 28.8% on CSC after age 65 compared to the 7.4% of 45-65 age category. The forecast suggests those over 65 on the CSC will rise from 845 to 1200 in the next 3 years, thereby making the scheme entirely unsupportable by the practice. What choice will we have but to entirely abandon delivery of equity in the primary care system? Are we moving to a primary care system where only the top 50 percent of income earners can access care at all?

Financial Impact

This significant deviation from the funding assumptions has led to a cumulative financial shortfall of $658,000 over the past three years for Silverdale Medical, with current monthly losses exceeding $12,000. The following image provides a visual representation of the escalating financial burden of supporting the CSC funding scheme:

The chart shows the cumulative financial difference over time, illustrating how the growing gap between funding provided and the actual cost of care is widening as utilisation rates related to the aging demographics continue to rise.

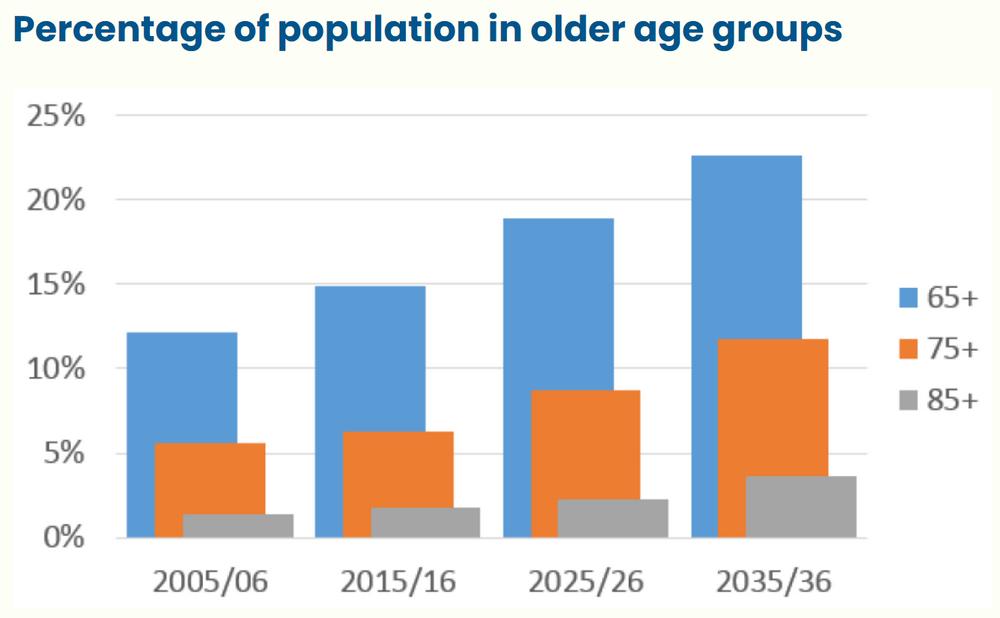

Demographic Shifts and Future Challenges

The financial challenges are expected to intensify as the proportion of CSC cardholders over 65 continues to grow. Currently, 28.8% of the over-65 population at Silverdale Medical hold a CSC card, compared to just 7.5% of those aged 45-65 who are still working. As the baby boomer generation ages and more retire losing their employment earnings – we expect that number of patients qualifying for the CSC card to dramatically expand. The number of high-demand patients is projected to increase significantly, further straining the financial viability of practices that are already struggling to manage the costs associated with this underfunded care model.

2. Equity of Access is critical to a well performing Primary Care system

The responsibility of government is to fund health, and sufficiently fund health equity to ensure all segments of the population can afford to access the health they need. Failing to sufficiently fund primary healthcare will result in patients not addressing health problems early when interventions can be small, manageable and be resolved with the best health outcomes.

Excellent primary care reduces hospital admissions, saves the health system money overall and improves health outcomes for the best population health. There are ample evidentiary articles and studies that demonstrate these facts.

The Ministry of Health and DHBs currently have a way of crowning some practices with additional discretionary funding, rather than effectively addressing an equity aware healthcare system that is nationally fair to all citizens and all health providers. The current processes dramatically favour large health corporations who use conflicted influence to put forward their own corporations’ financial self-interest with health authorities. While smaller, less influential players who serve their population well are grossly underfunded for the impact and achievements of their work. The ministry’s goal however should be a health system that is devoid of undue influence, that brings forth health equity, accountability, and good governance of healthcare funds – and ensures that what is paid for by the public purse to contracted health agencies is delivered for the public good.

Equity should follow the patient – this means individual practices do not get funded to provide a different level of equity – such as the failed Very Low-Cost Access (VLCA) model. The VLCA model pays a premium because the practice is deemed to serve a low-income community. However, the classification of the community means that some people who are very wealthy in that community get access at the low-cost rate, while people who live in a different community but are still of significant equity need do not get such affordable access in their own community. Some very wealthy people travel far and access enrolment in VLCA practices. Additionally, some VLCA practices dramatically under service their population, but still attract significant enrolments due to the low-cost fee access. At the same time, these practices also face the problem of unnecessary overuse. The practices that dramatically underserve the health needs are currently the most profitable practices in the country.

Addressing these problems is imperative, is tremendously overdue, and must not be overlooked any longer.

A more uniform, strong policy-based national system should appropriately identify the “patient” as in need of equity support. The concept of support should be stratified to fund those with higher needs (both medical and financial) at a higher level than those with lower needs. But the system must recognise more than one level of need. By funding being attached to the patient in need – all patients can access care where they believe themselves, that they will get the best care and will result in reduced enrolments/funding being delivered to practices that fundamentally underserve their enrolled population. Empowering the patient’s right to choose their healthcare provider is a critical quality factor.

Funding should be based on the patient’s income and net worth rather than just income as is the current CSC qualification process. Increasingly in society there is a distinct separation between income and net worth. Those with low income are not necessarily poor. There are several high-net-worth individuals who own multimillion dollar properties and drive luxury vehicles who borrow against their assets to pay living expenses while keeping assets in corporations. These individuals still personally qualify today for the CSC card. These people should not benefit from higher levels of funding intended to address equity disparities. A qualification for equity should ask “Do you own your own home? If so, what is the address? Do you own a vehicle? If so, what make, model and year. These are things wealthy people own and the value of which can be assessed. Requalifying should happen at regular intervals of 2-3 years.

Recommendations for Equity Funding

To address these challenges, equity funding should be adjusted to differentiate between two critical categories:

-

Abject Poverty (CSC Level 1): Patients with little to no income or assets. It is recommended that they be fully funded for up to 4 GP (General Practitioner)

appointments and 2 RN appointments per year, with patient fees set at $25 per GP visit and $10 per RN visit. Additionally, each CSC Level 1 patient should attract $550 in additional funding to cover the higher costs associated with their care and offset the fee differential.

-

The Working Poor (CSC Level 2): These patients, who earn less than the full-time living wage and have limited assets (e.g., less than $100,000 in personal assets such as home equity or a car), should be funded for 4 GP appointments and 2 RN appointments per year. Their patient fees should be limited to $50 per GP visit and $20 per RN visit. Each CSC Level 2 patient should attract $440 in additional funding to reflect their lower but still significant healthcare needs.

3. Funding Health Status

Some patients genuinely are high needs due to their unique health situation. These patients might have 8-12 appointments in the year for legitimate health needs. Diagnoses like cancer, asthma, significant mental health, multiple chronic health comorbidities require more visit per year. But these situations sometimes more or less burdensome at various times. Patients in these situations need “health equity” support that is flexible, available to those that need it when they need it, and not expended or paid for when it is not needed. There should be a way for the practice administer funding to help patients facing a significant rightfully required use to address the patient fees associated with those additional visits.

Currently some practices have some discretion with the use of “Flexible Funding.” The practices have a budget to address these types of health status problems but must report who received this support and for what equity purpose. If practices are claiming against the fund to address these health complexities, this should be supported. The clinicians who are caring for these patients know who needs the support, and how best to use these funds to address health inequity.

4. Addressing the risk of Overuse

To prevent overuse, measures should limit the number of fee-limited funded appointments available annually. By limiting the number of fee-limited funded appointments available annually will encourage the patient to have judicious use of health resources. While the Health Status funding will allow health providers to address the limited set of circumstances where greater access is clinically required. For example, the fee limited funded appointments for CSC Cardholders and Free appointments for children under 13 might be limited to 4 in a calendar year. This measure will ensure that the cost of serving these contracts is not an unjust burden on the practice. As well as ensure the government funding covers the cost to deliver. This measure will also allow clinicians to carry a higher enrolment load. As the country faces a national shortage of doctors, this strategy will extend care to more patients. If a patient moves their enrolment, the number of appointments available for the year should follow them to the next practice. Such a measure of use will also give the government better understanding of the use of services across communities, ethnicities, and economic statuses. This data over time will provide better information to the government to fine tune primary care policy.

5. Inequities in Capitation Payments and the Need for Accountability Capitation Without Service

There is growing concern over practices that receive capitation payments for patients they are not actively serving. Some patients, unable to secure appointments at their enrolled practices, are forced to seek care from virtual service providers at their own expense. This not only undermines patient access to care but also represents a misuse of public funds intended to provide for comprehensive primary care.

Proposed Accountability Measures

To address this, robust accountability measures should be introduced to ensure that practices receiving capitation payments are indeed providing the expected level of care to their enrolled patients that the contract demands. One practical solution is to adjust the General Medical Services (GMS) payment system. If a practice fails to provide care, a more relevant to a single visit proportion of their capitation payment should be transferred to the practice that delivers the service. This would incentivise practices to meet their service obligations and ensure that public funds are allocated to providers genuinely serving patients.

6. Disillusionment in the Primary Care Sector

Growing Disillusionment Among Primary Care Providers

Disillusionment is becoming increasingly prevalent among primary care providers, leading to early retirements, career changes, and an exodus from the country. This disillusionment is deeply rooted in the perception of being undervalued by the Ministry of Health and the existing funding models. Primary care professionals, who play a crucial role in the healthcare system, feel that their contributions are not adequately recognised or rewarded compared to their counterparts in the secondary care sector.

Financial and Operational Burdens

Unlike hospitalists, who benefit from fully funded facilities, support systems, and equipment provided directly by the Ministry of Health, primary care providers must shoulder significant financial and operational burdens. They are required to advance substantial capital to establish clinical spaces, equip their clinics, and fund full operations. As a result, while primary care funding may appear significant on paper as personal income, the reality is starkly different.

General practitioners (GPs) in primary care often see only 40-50% of the funding paid as actual earnings, with the remainder covering the costs of running their practices. In contrast, hospitalists’ earnings represent 100% of their income, as all associated costs are absorbed by the healthcare system.

Funding Must Keep Up with the Cost of Living

Eighty percent of revenue earned by practices is spent on staff wages. It is critical that funding schemes are benchmarked to the cost of living. When wages for health workers in New Zealand do not keep up with other comparable countries (Australia, Canada), then New Zealand loses health workers. The COLA annual adjustment should be directly contracted.

Primary Care Provider Made the Keeper of the Patient’s Health Record

With the introduction of practice management software, the primary care doctor became the holder of the Patients’ Health Record. Historically, each doctor kept the records of their own clinical services. Now the expectation is that the primary care clinic must keep the patient’s full medical record. The problem is that now the primary care doctor is expected to read, process and manage the entire record, bear the clinical coordination responsibility, and is responsible for everything found in it. This large and high-risk burden is not funded in any way. While the funding calculates at an average of 2.2 visits per year, it provides nothing for the time and effort required to provide the full coordination and leadership role. The practice must also be the provider of all these records to courts, to patients. The full costs of the technology and associated administrative burdens to serve this function are also not funded.

‘Dumping’ on the Primary Care Provider

Increasingly it is impossible to find specialists to accept the care of ongoing complex medical conditions. Historically if a patient had advanced diabetes and heart disease that patient would have a cardiologist and an endocrinologist that managed those conditions. Now the specialist will see the patient as a single consult, and then send the ongoing management back to the primary care doctor, along with a list of things to monitor and check throughout the year. While the specialist benefited from a highly lucrative consult fee, the primary care physician faces increasing losses from accepting the responsibility to provide an additional 3-5 appointments at the funded rates with no additional funding from government.

7. Ensuring Comprehensive After-Hours Care in Primary Care Contracts Current Challenges in After-Hours Care

The current primary care contract requires practices to support their patients 365 days a year, including evenings and weekends. However, most practices do not provide after-hours care. Instead, many refer their patients to the Telehealth Service provided by the Ministry of Health, which, while valuable, does not fully meet the expectation of in-person care. This gap in service is particularly problematic for patients who require immediate, hands-on medical attention outside of regular office hours.

Proposed Solution: Separate Funding for After-Hours In-Person Care

To address this issue, the primary care contract should be revised to separate medical funding specifically for evenings and weekends in-person care. This funding would be allocated to practices that either deliver this care directly or assign it to a designated after-hours service provider within a reasonable distance—10 km for urban practices and 30 km for rural practices.

Requirement for Accessible In-Person Care

Under this revised contract, to receive the allocated funding, practices must ensure that their patients can access in-person care 7 days a week, 365 days a year, from 8 am to 8 pm at enrolled fee rates. This approach allows for flexibility in how practices meet their contractual obligations. For instance, a group of practices could designate a local Urgent Care center as

their after-hours service, providing a reliable and accessible option for patients in need of urgent care during evenings and weekends.

Balancing Access and Funding

It is essential that this funding does not mandate free after-hours service, as this could inadvertently encourage patients to delay seeking care during regular hours to avoid general practice fees. Instead, the goal is to ensure that patients have access to affordable, in-person care at any time, without compromising the viability of daytime services. Health workers are paid a premium to work evenings and weekends, so the system must encourage patients to seek care during the business day. The Ministry of Health should establish clear guidelines and sufficient funding to support these after-hours services, ensuring that patients receive consistent and continuous care, regardless of when they need it.

Recommendation

The Ministry of Health should revise the primary care contract to include dedicated funding for after-hours in-person care. This funding should be contingent upon practices providing or arranging accessible in-person care for their patients 365 days a year, ensuring that after-hours services are integrated into the broader healthcare delivery system. By doing so, the Ministry can ensure that all New Zealanders have reliable access to the care they need, when they need it.

8. Impact of Government Policies on Small Businesses

Primary care clinic across New Zealand is small business. Government policy that is detrimental to small business is detrimental to primary care. Tax compliance, local ordinance, access to capital investment, and ever-increasing compliance factors crush small business.

The Holiday Act of New Zealand is very detrimental to business that must employ part-time workers; because sick leave entitlements, and statutory holiday entitlements that are not earned based on the hours worked in the business. Yet the primary care workforce is aging and seeking part-time arrangements. All entitlements should universally be earned based on the hours worked to better support employers to engage part-time workers.

Conclusion and Call to Action

New Zealand’s primary care sector is at a critical juncture. The current funding model for CSC holders, compounded by inadequate adjustments below the Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA), is outdated and fails to meet the actual service demands, leading to significant financial strain on practices like Silverdale Medical. The lack of accountability in capitation payments, the growing disillusionment among primary care providers, the broader regulatory challenges— including disparities in compensation and barriers to entry for skilled healthcare workers—and the need for rapid development and integration of allied health professions are all undermining the viability of primary care across the country.

The consequences of inaction are clear:

-

Erosion of Primary Care Services: Without immediate intervention, the primary care sector will continue to deteriorate, leading to reduced access to essential services for New Zealanders, particularly those in vulnerable communities.

-

Exodus of Skilled Providers: The ongoing disillusionment among primary care professionals will drive more experienced providers to retire early, leave the country, or pursue alternative careers, exacerbating workforce shortages.

-

Widening Health Inequities: The current inequities in funding and compensation will continue to widen, disproportionately affecting low-income and rural populations who rely heavily on primary care services.

-

Inadequate After-Hours Care: The failure to provide comprehensive after-hours care leaves many patients without necessary access to in-person medical attention during critical times, undermining the promise of continuous care in the primary care contract.

The Ministry of Health must act decisively to address these challenges. We call on the Ministry to:

-

Implement an equitable and sustainable funding model that accurately reflects the actual costs of delivering primary care services, considering the growing demands and the need for proper compensation adjustments that keep pace with inflation.

-

Standardise compensation across the healthcare system to ensure that primary care nurses and doctors are fairly compensated for their skills and contributions, with appropriate recognition for those who work evenings, weekends in Urgent Care centres.

-

Enhance accountability in capitation payments to ensure that funding follows the patient and supports practices that genuinely deliver comprehensive care to their enrolled populations. Practices that fail to meet the needs of their enrolled patients should see a proportion of their capitation payments reallocated to those that are actively serving their communities. Rewarding practices that effectively serve their patients is essential for maintaining quality care standards of care across the board.

-

Address regulatory barriers that affect small primary care businesses, including revising the Holidays Act to address fair entitlements to part-time workers and simplify the immigration and professional licensing processes for skilled healthcare workers.

-

Invest in the development and integration of allied health professionals into primary care. Rapidly expand training programs and create funding pathways that support the inclusion of Physician Assistants, Nurse Practitioners, Dietitians, Clinical Pharmacists, Psychologists, and Clinical Counselling Social Workers in primary care teams. This will enhance the capacity and effectiveness of primary care, ensuring it can meet the diverse needs of New Zealand’s population.

-

Revise the primary care contract to include dedicated funding for after-hours in-person care. Ensure that patients have access to in-person care 7 days a week, 365 days a year, from 8 am to 8 pm, through either direct provision or through delegated commission with local Urgent Care centres. This approach will uphold the integrity of the primary care system and fund the agencies providing the afterhours care.

These actions are not just recommendations—they are necessities. The health and wellbeing of New Zealand’s population, particularly its most vulnerable, depend on the resilience and effectiveness of the primary care sector. It fundamentally should not be that the practices that provide the worst quality service are the most profitable in the country. The Ministry of Health must lead the way in implementing these changes to safeguard the future of primary care and ensure that all New Zealanders have access to the quality healthcare they deserve.

References

1. Ministry of Health – NZ Health Statistics Our Changing Population -

2. We need more primary care physicians Here’s why and how. Sheridan, N., Love, T., Kenealy, T. et al. Is there equity of patient health outcomes across models of general practice in Aotearoa New Zealand? A national cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health 22, 79 (2023).

3. Closed books/Ceasing Enrolments: Pledger Megan, Irurzun-Lopez Maite, Mohan Nisa, Jeffreys Mona, Cumming Jacqueline (2023) An area-based description of closed books in general practices in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Primary Health Care 15, 128-134.

https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/for-health-professionals/data-and-statistics/nz-health-statistics/health-statistics-and-data-sets/older-peoples-health-data-and-stats/our-changing-population/

Our Changing Population – Health New Zealand